PIʹLEUS or PIʹLEUM (Non. Marc. iii; pilea virorum sunt, Serv. in Virg. Aen. IX.616), dim. PILEʹOLUS or PILEʹOLUM (Colum. de Arbor. 25); (πῖλος, dim. πίλιον, second dim. πιλίδιον; πίλημα, πιλωτόν), any piece of felt; more especially, a skull-cap of felt, a hat.

There seems to be no reason to doubt that felting (ἡ πιλητική, Plat. Polit. ii.2 p296, ed. Bekker) is a more ancient invention than weaving [Tela], nor that both of these arts came into Europe from Asia.

From the Greeks, who were acquainted with this article as early as the age of Homer (Il. X.265) and Hesiod (Op. et Dies, 542, 546), the use of felt passed together with its name to the Romans. Among them the employment of it was always far less extended than among the Greeks. Nevertheless Pliny in one sentence, "Lanae et per se coactae vestem faciunt," gives a very exact account of the process of felting (H. N. VIII.48 s73). A Latin sepulchral inscription (Gruter, p648, n4) mentions "a manufacturer of woollen felt" (lanarius coactilarius), at the same time indicating that he was not a native of Italy (Lariseus).

The principal use of felt among the Greeks and Romans was to make coverings of the head for the male sex, and the most common kind was a simple skull-cap. It was often more elevated, though still round at the top. In this shape it appears on coins, especially on those of Sparta, or such as exhibit the symbols of the Dioscuri; and it is thus represented, with that addition on its summit, which distinguished the Roman flamines and salii, in three figures of the woodcut to the article Apex. But the apex, according to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, was sometimes conical; and conical or pointed caps were certainly very common.

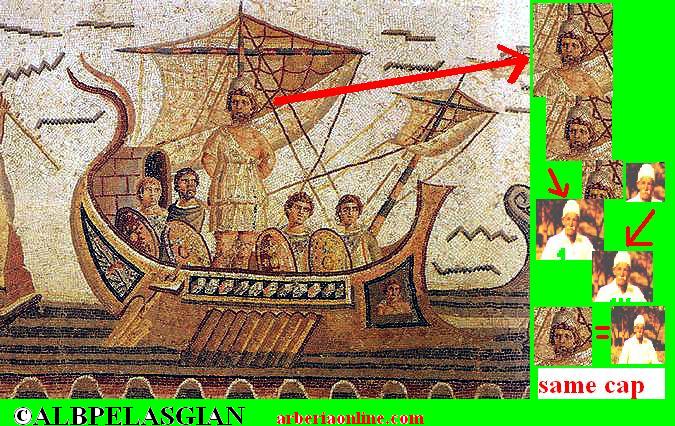

In the Greek and Roman mythology different kinds of caps were symbolically assigned to indicate the occupations of the wearers. The painter Nicomachus first represented Ulysses in a cap, no doubt to indicate his sea-faring life (Plin. H. N. xxxv §22).º The woodcut on the following page shows him clothed in the Exomis, and in the act of offering wine to the Cyclops (Winckelmann, Mon. Ined. ii.154; Homer, Od. IX.345‑347). He here wears the round cap; but more commonly both he and the boatman Charon (see woodcut, p512) have it pointed. Vulcan (see woodcut, p726) and Daedalus wear the caps of common artificers.

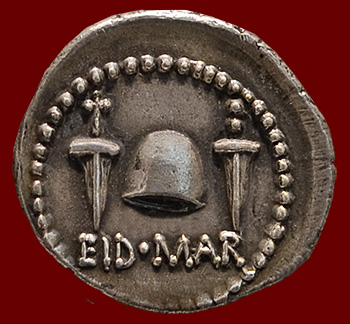

Among the Romans the cap of felt was the emblem of liberty. When a slave obtained his freedom he had his head shaved, and wore instead of his hair an undyed pileus (πίλεον λευκόν, Diod. Sic. Exc. Leg. 31º p625, ed. Wess.; Plaut. Amphit. I.1.306; Persius, V.82). Hence the phrase servos ad pileum vocare is a summons to liberty, by which slaves were frequently called upon to take up arms with a promise of liberty (Liv. XXIV.32).

The figure of Liberty on some of the coins of Antoninus Pius, struck A.D. 145, holds this cap in the right hand.